To the End of the Earth

They say that your Camino, your way, begins long before you step foot in France.

A series of choices, sandwiched between life’s peaks and valleys, pulled you to begin a pilgrimage on foot across the country of Spain.

It took me days to get there, to Saint Jean Pied De Port, a commune in Southwestern France. After three planes, two buses and a train, and one very serendipitous car ride, I found myself in this quintessential French, tiny town. Saint Jean is nestled deep inside of the Basque Country, a land filled with terracotta roofs, cobblestone streets, singing peasants and infused with the scent of warm baguettes.

With high-test European whimsy.

But really, it took me years to get there.

“Not I, nor anyone else can travel that road for you. You must travel it by yourself. It is not far. It is within reach. Perhaps you have been on it since you were born, and did not know. Perhaps it is everywhere- on water and land.”

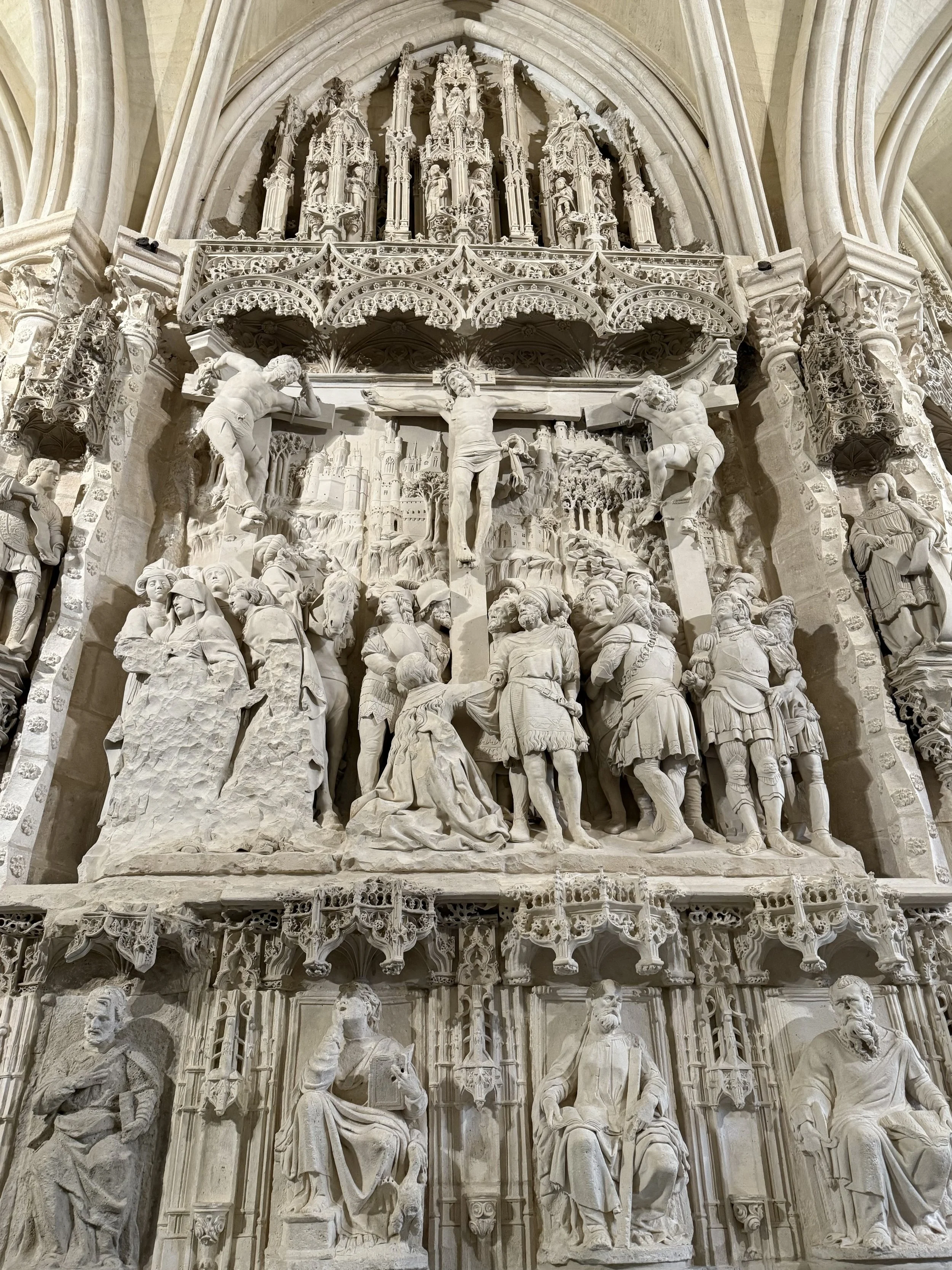

The Camino de Santiago, or “Way of St. James”, is a network of walking paths spidering across Europe. Each lead to the grand cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in northwestern Spain, the burial site of the apostle James and where his ashes are still kept beneath the main altar. Historically a significant Christian pilgrimage, the Camino originated in the 9th century after the discovery of St. James’s tomb, and today it is traveled for a rainbow of reasons.

For some, religious.

Others, spiritual.

Could be a cultural craving, a physical challenge, or a mental milestone.

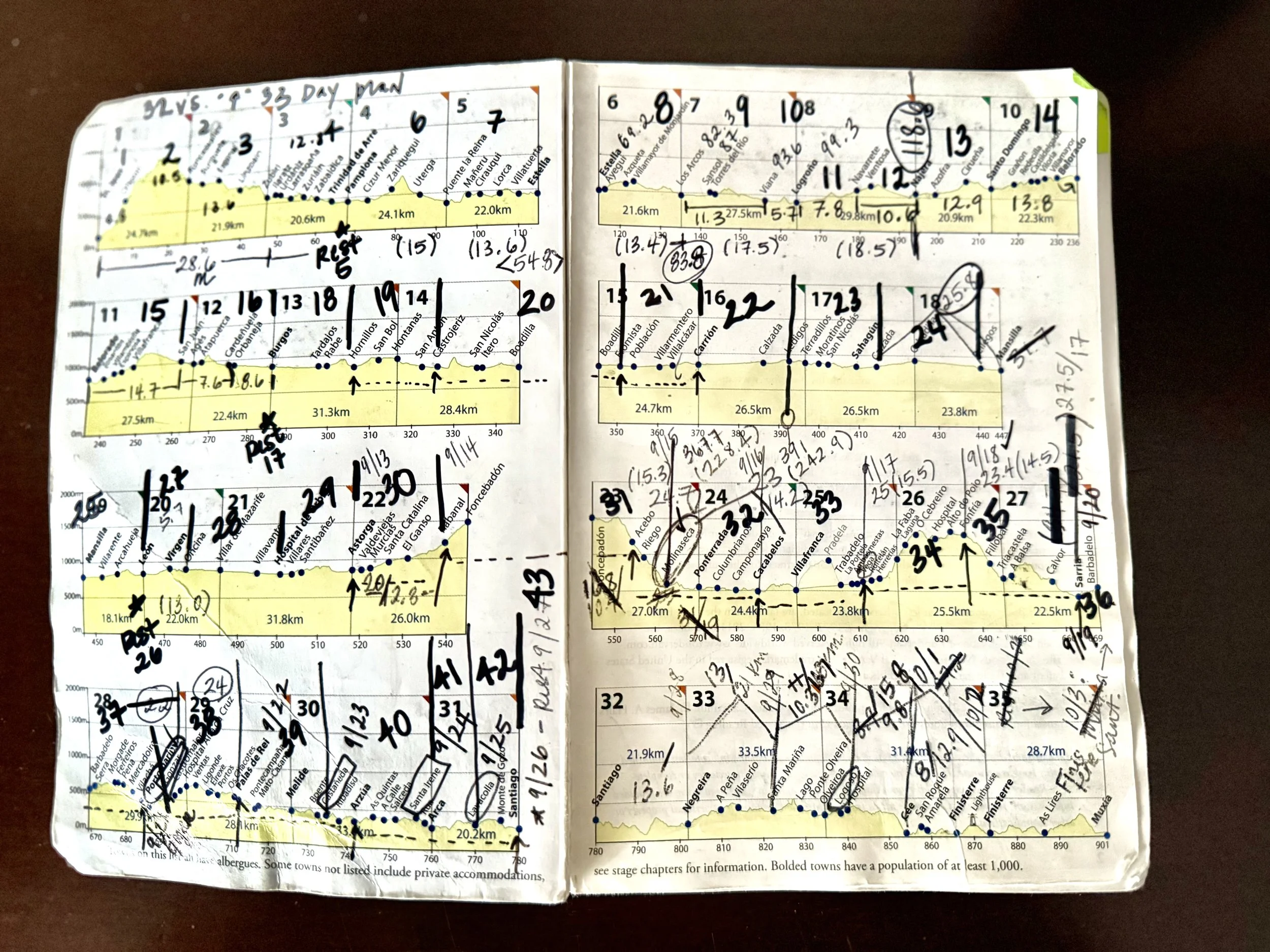

The Camino Francés, the French Way, is the most traveled route and deeply rich in its mountains, meseta, vineyards and villages, alike. The Francés stretches about 800 kilometers (or 500 miles, for us Yankees) from the French Pyrenees mountains to the city of Santiago, Spain. Between hostels and chapels, I relied on cemented scallop shells and painted yellow arrows to show me the way.

The way to Santiago de Compostela.

And the way to the answer of a question.

“Why are you…here, Sarah?”, my first evening in Saint Jean was met with a very direct, yet complicated one.

Joseph was the innkeeper of Gite Beilari, the charming 17th century hostel that welcomed me to France. Beilari is quietly tucked into the climb of Rue De La Citadelle, warmly receiving hikers from all corners of the world with its rest and its homemade vegetarian meals. I twirled my pasta with scrambled egg and pushed the creamy cucumbers around my plate with my fork as I tried to join in conversations with the other pilgrims sitting around the table. They were from South Africa and Australia and Germany. Paris. Poland. And Portugal. Places that I had never been before. Their languages grazed over the baskets of bread and they swirled around the bottles of wine like music. My company was worldly. Sophisticated. They were bilingual. Trilingual. They were all of the linguals. They talked of their tales of travel and time spent abroad. Their study in the Netherlands and their flats in London. They spent their summers in Porto and their winters in Rome.

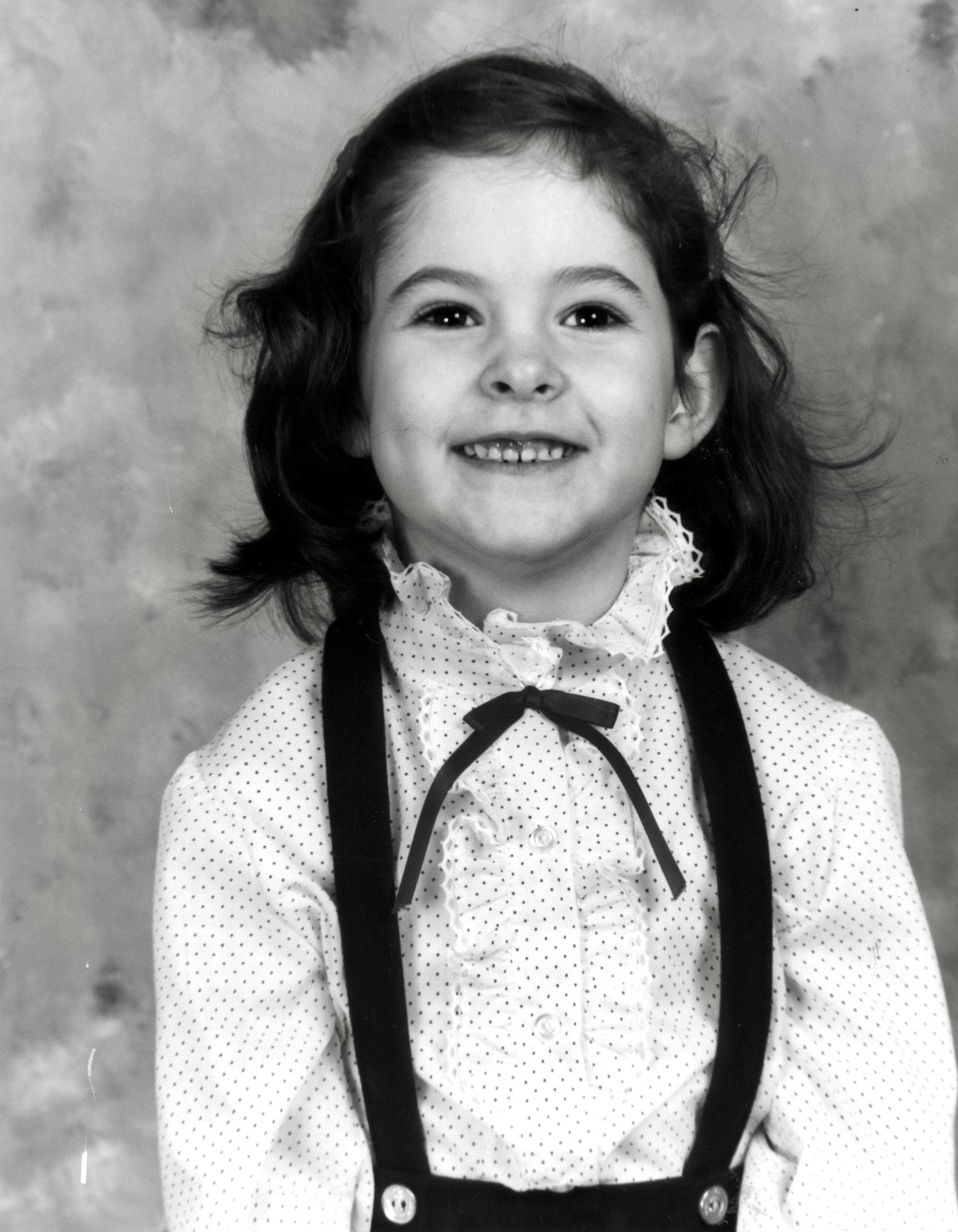

I vacationed to Kennywood as a kid, an amusement park that was a stone’s throw from our apartment. My anticipation would beat against the window of Dad’s Ford at my first glimpse of the Steel Phantom’s chain lift, sitting high over the Mon Valley. Because roller coasters felt like freedom and their company meant that we had enough money to buy Potato Patch fries.

The people sitting next to me at dinner that night in Saint Jean Pied De Port completely fascinated me. Their confidence fascinated me. Their love affairs with the world fascinated me. Their clothing, their subtlety and their unhurriedness fascinated me. And it fascinated me that they didn’t seem to feel like me, lost and alone in a foreign land.

Their energy pulled me closer like a magnet the size of the Titanic.

But I felt undersized.

Like a tiny, little broken-finned fish in a very big and mystical pond.

Like an 8-year-old girl, showing up in grown-up’s clothes.

Once again.

The same way that I felt when I took my first steps towards Maine, surrounded by seasoned vagabonds and learning how to swim on the Appalachian Trail.

Joseph was asking me a very important question.

And one that I didn’t know the answer to.

I didn’t know why I was walking the Camino.

“To walk alone without a plan.”, those six words flew from my mouth as if they were riding on a pigeon carrier without my permission.

“But, haven’t you already damned done this, Sarah?”, my inner monologue fought with my response, it was confused.

I was always a hitch and a bus ride away from home on the Appalachian Trail.

But now, I was over 4,000 miles away, beyond the sea and without my tent.

Relying on hostel-hopping intimidated me. I felt safer, in control, when I was carrying my shelter on my back, dinner in my bear bag and counting on the creeks to quench my thirst.

Now it was time to trust that what I needed would find its way to meet me at the end of each day.

I had to shed another layer of my insecurity.

And therein, laid my fear.

“A ship in harbor is safe, but that is not what ships are built for.”

Joseph followed, “But, you must be walking with a group…or a friend?”

I was not.

I felt timid, excluded, without a clan to fold into.

Three days later, I walked out of Zubiri as the sun rose and the jamón settled with the espresso in my stomach. I saw a young, bright blonde-haired girl sitting with her arms hugging her knees on the shore of the Arga River as I crossed the Puente de la Rabia, the “Bridge of Rabies”. Her curls bounced in the wind, they were the size of my fists. As she began to write in her journal, she pushed them from her face with her pen. She wrote in between her thoughtful stares across the water and the gusts of wind that tried to pull her mind somewhere else.

She looked complete in her solitude, as if she would have turned clan after clan away to protect her peace, even if they had offered her a magic carpet ride to Santiago.

And things began to make sense.

All that I needed was me.

I inhaled my own alone as I ascended from the Río Arga valley, stopping for water from fountains made of ancient Catholic concrete and for cañas with bocadillos along the way. The beer tasted smoother and the bread felt softer on the Camino. I joined the clans of sheep as they made melodies with their bells and their baas at mountain crossings. I drank glasses of fresh squeezed zumo naranja, and I filled my backpack with hunks of aged cheese and grapes picked straight from the vine for later. I spent my days walking alone with my mouth closed and my ears wide open. I was just being a sponge. A student of the Camino.

And I was okay.

Back in my Kennywood days, no one told me that I was going to be okay.

Through Pamplona and Estella and Logroño, I walked. I maneuvered my way through gold-gilded churches, primeval city walls and the legends of Spain’s past. And I met people. I met so many people. People whose deep minds and kind hearts matched the beauty of the scenery that surrounded me.

People who found their way to meet me exactly when I needed them.

Exactly when I was ready for them.

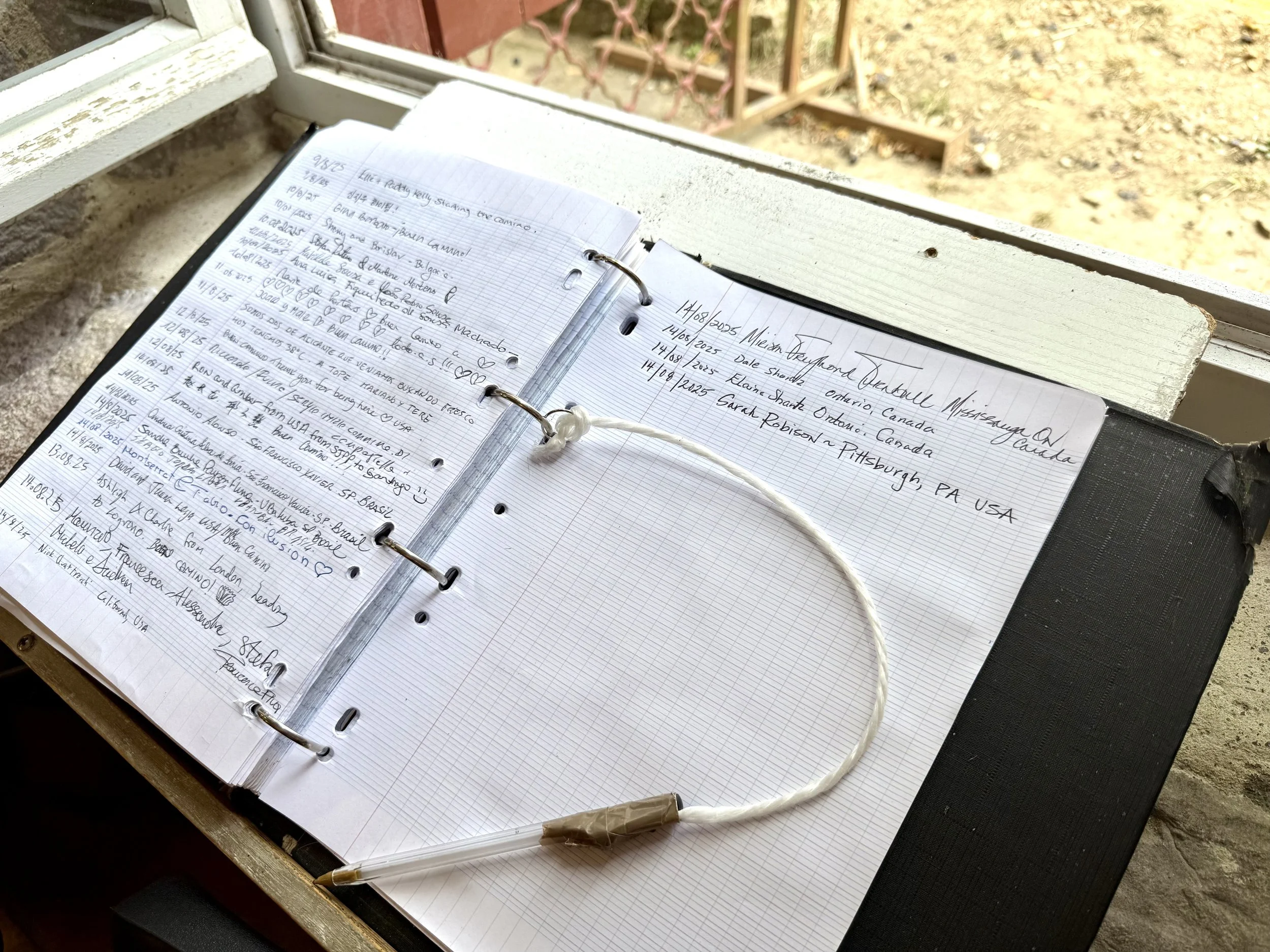

First, there was Mikel.

Mikel, an Appalachian Trail hiker and from Pamplona, first hand understood how it felt to walk alone in a foreign land. And then, Marina and René. They had only met one another hours before, on the train to France from Germany, when I offered Marina my chair on the patio of Le Kawa. They were my first friends. I shared a bedroom with Ruth and Tiffany, a mother and daughter from Seattle. Bob and Josie’s dedication to one another showed me what I am seeking in a partner. Dallas was soft-spoken but quick on the uptake. We struggled to make our way over the Napoleon Route in the crippling heat together. Juergen was raising money for charity and had walked all of the way from Germany. Jeronimo. Jeronimo was blind. And I guided him down the west side of the Pyrenees and into Roncesvalles, arm in arm, using only our voices and our feet to communicate with one another. Brian and Gary were Camino savants, rich in their Chistian faith and from California and Colorado, respectively. I drank my first cold beer with these two, our mugs colliding with the setting sun over the peaks of the Pyrenees. Sonny, Hanle and Aniek. Korea, South Africa and the Netherlands. We were ages apart but aligned from the start. And Tom and Mark. Tom and Mark shined with their love for one another over breakfast at Casa Sabina when we were assigned to the same table. And over croissants and the upcoming weeks, we morphed into a family. I met Olga and Pierre after leaving Larrasoaña. They lived in Valencia and offered their home to me after only five kilometers together. Kristina and Nils-Erik came from Sweden. They were warm and funny and delightful. They felt like a hug. Vicki and Ben, we kept finding one another in the most unexpected of places as if something far bigger than us wanted to keep us together. Ben would call out to me from the center of plazas everywhere in his brazen Danish, Canadian mix, “Where ya been, for fucks sake?!”, and Vicki’s arms felt like home when I ran to their table and fell into them. These two were my other halves, my best buds and my confidants. Eric was a gentle giant, and Diane, a miniature powerhouse. And Stacey and Marve. These four were Pennsylvania. They felt like Pennsylvania. They felt familiar. There was Clare. And Leti. Daniella. And Julio. Helena, my forever dinner date and Sabine, her journey cut too short. I gave Sabine my last piece of fruit because she lost her wallet. Grayson. Isy. Izik. And Faith. I noticed an ‘11:11’ tattoo on Faith’s right forearm as we were walking out of Viana and entering the La Rioja valley. We had never met. “Hey! Excuse me!”, I called ahead, not knowing if she spoke English, but it was worth a try. I had to tell her that I had a matching one. That it was my angel time.

Faith and I talked about trauma bonds and body. We talked about addiction and abuse. About family and failed relationships. I shared things with Faith that day as if I was in confessional. And Faith freed me.

The Camino tells no secrets.

And then came Falk.

Falk was poker-faced as I approached him. I was on my way to Navarette, and he was sitting on a park bench with a brace on his right knee and a cigarette in his left hand.

He was all stone and stoicism.

I placed his name in my memory bank after we introduced ourselves, and I said, “Danke”.

It was the only German word that I knew.

“Bitte”, he replied.

And then, I kept going.

The next evening, we found ourselves sitting at the same table outside of Puerta de Nájera.

Falk was anything but deadpan. He surprised me. He was calculated, but warm. He was interested, and interesting. He was confident, yet soft.

So I offered him the rest of my Ensalada Mixta.

And he accepted.

Through Azofra and Santo Domingo and Belorado, we walked, Falk and I. We talked about the contrast and similarities of German and American food and family traditions. We asked each other the hard questions. We made up a word game to pass the time. Each round proved to be good for a solid three miles. He fed me packets of sugar when the sun got the best of me and I was back down and belly up in the dirt of the Roman Way. And I bartered for ice at a bar in Cee when he so desperately needed it for his ankle after we descended into the fishing village.

“Sí! We finally see the sea in Cee!”, we chanted at our first glimpse of the Atlantic ocean through the trees. I inhaled the salty air as I exhaled the miles to my back.

As I exhaled my years of Kennywood past.

Falk taught me what I could not have learned alone.

“We’re all just walking each other home.”

I walked. And I ate. I drank wine, and I broke bread. I then I walked again. And again. And again. And, again. I watered my thirst and fed my soul. And broke more bread. I learned languages unfamiliar. I laughed. And I cried. I saw places. So many special places. I met peace for the first time. And patience. And pause. And I prayed. Oh, how I prayed. I bandaged my blisters before eating more bread. The warmest bread imaginable. I embraced monotony. And meditation. I listened to the music. And not the choreographed kind. I witnessed bliss. And walked even farther, after eating again. And then I drank more wine. I grew to understand gratitude in its simplest form. And I slept. I slept so soundly. Only to repeat again, the next day.

“Essentially, this thirst is not the longing for an extensive walk on the Camino. It’s the longing of meeting your own being, outside the temptations of a fully materialistic world. Camino is just a channel, a concrete representation of your inner need to evade the loop your life is repeating over and over again, and find your true nature, your true voice, your true meaning on this planet. And when you walk this path, you complete a layer of your search.”

When we experience new things, we can’t prevent the impact that they will have on our tomorrows. We cannot go back to our previous dimensions. Our outlook permanently bends, like steel, incapable of returning to its original shape.

But what is the alternative?

To stay in the harbor?

No.

We fucking set sail.

And Santiago de Compostela did not feel like the end.

And so I kept walking for 60 more miles, through moss and fog and mystical green landscapes. I woke up to singing roosters, and I fell asleep with the last of summer’s sun.

I kept walking to the end of the earth.

To Finisterre.

Its name derived from the Latin, finis terrae, meaning “end of the earth”, Finisterre was believed to be the westernmost point of the known world by the ancient Romans. The threshold where the land ended and the uncharted ocean began.

The place where the lighthouse lives.

Where you can stare out into the abyss of the wild Atlantic as it crashes against the stone cliffs of Monte Facho and meet your moment. The moment when I could say that I walked from France to Finisterre. The moment that I was able to answer Joseph’s question, “Why are you here, Sarah?”

“I don’t want to feel like the 8-year-old girl dressed up in grown-up’s clothes anymore.”, that was my answer.

On September 23rd, Falk and I walked into Castañeda after sunset, weary and hungry. The canvas green awning of Santiago Hostel was bleached from the sun and older than dirt, but it had promise of dinner and a bed. José stood behind the bar, pieces of breakfast, lunch and dinner still living on his white apron. Sweat trailed from his temple to the phone receiver that he was squeezing between his ear and his shoulder while he wiped the bar and took a reservation at the same time.

“Why are you so late?!?”, he barked as soon as we walked through the curtain of wooden beads that he used for a front door.

“Why am I so ‘late’? Because today I was forest bathing and eating bananas with chocolate. The chocolate that we have been carrying since Astorga. We sat on a little bridge and dangled our legs over a quiet creek while we laughed. And we stumbled upon a meditation retreat named “Wisdom of the Way”, and the caretaker there brought us fresh cinnamon cake and coffee and water steeped with marigold flowers. Falk made his way thru a labyrinth that led to a treasure chest while I napped on a daybed made of pillows covered in sequins and Spanish tapestry. The breeze kept me in a light sleep, and I listened to a British father teach his young son how to play the guitar. I wasn’t certain if they were across the room from me or in my dreams. This moment in time gave me this overwhelming sense of wonderment for “where” I “was”, contrasted to where I had come from. I was alone, deep inside the mountains of Galicia, sleeping on a couch in Terra de Luz at two o’clock in the afternoon on a Tuesday. I didn’t feel like the tiny, little broken-finned fish in a very big and mystical pond anymore. I was learning how to swim, José. This is why I am ‘late’.”, I thought.

José was the cook, the cashier, the handyman and the housekeeper of Santiago Hostel. And he stayed up that night so that we could have a warm meal and clean sheets. He was exhausted too.

“Thank you, José. Thank you so much for helping us. It has been a long and winding road, and I am very sorry that I am late.”

“We don’t see things as they are, we see them as we are.”

As we prepare for the new year, let’s keep our finish lines moving. Let’s learn to love our 8-year-old selves. Put your arms around her. Introduce yourself and get to know her. Begin to understand her. Thank her for being so strong, for making it out alive. Then grab her by the hand and guide her. Pull her into your knowing. Because you know what to do now. Tell her that she can walk across Spain or change her own tire or sing karaoke. Or all three. And tell her that she can just sit quietly by herself too, because she doesn’t have to be afraid anymore.

Tell her that she can walk to the end of the earth.

Let’s keep walking, to the end of the damn earth and even farther. sweet girl.

I am, because you are.